You see your life passing right before your eyes as you live it

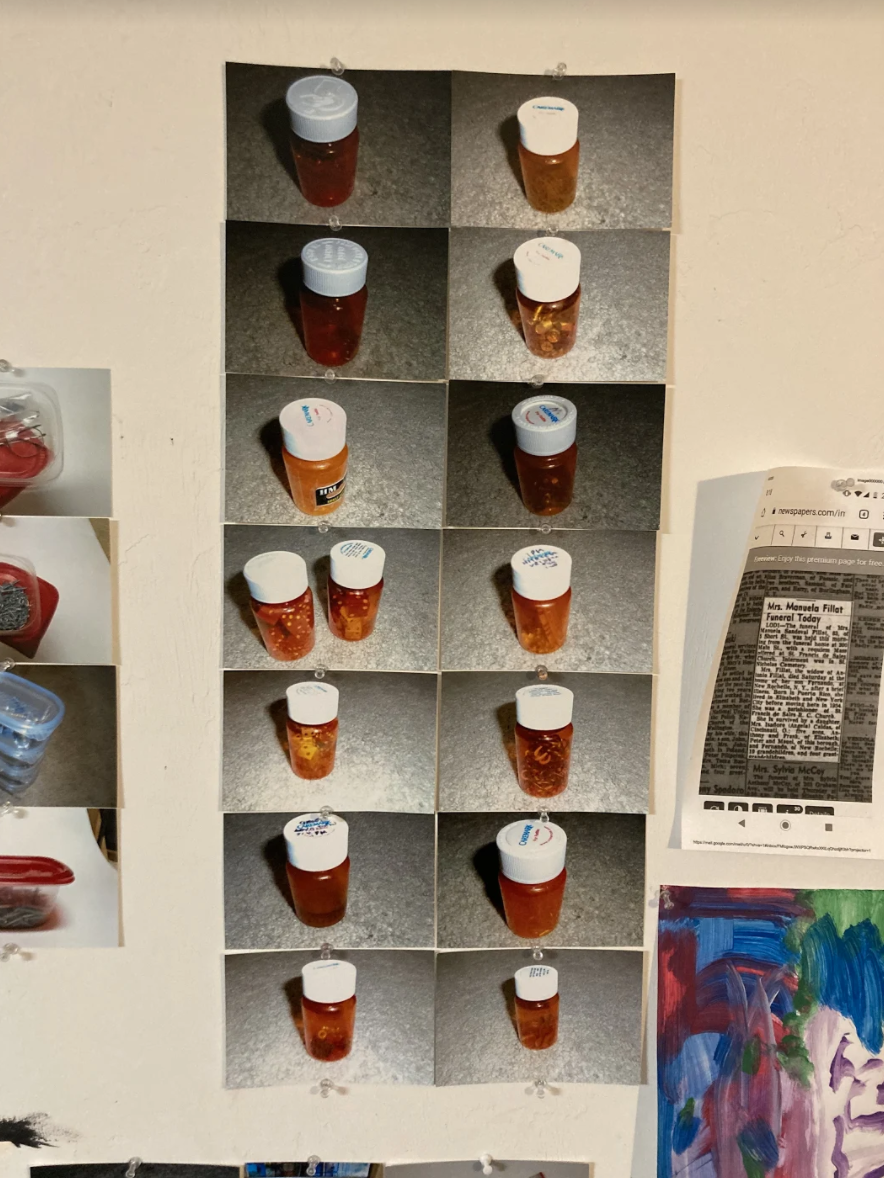

studies for you see your life passing right before your eyes as you live it 01

studies for the family

I am a Bad Puerto Rican (a joke, but still…)

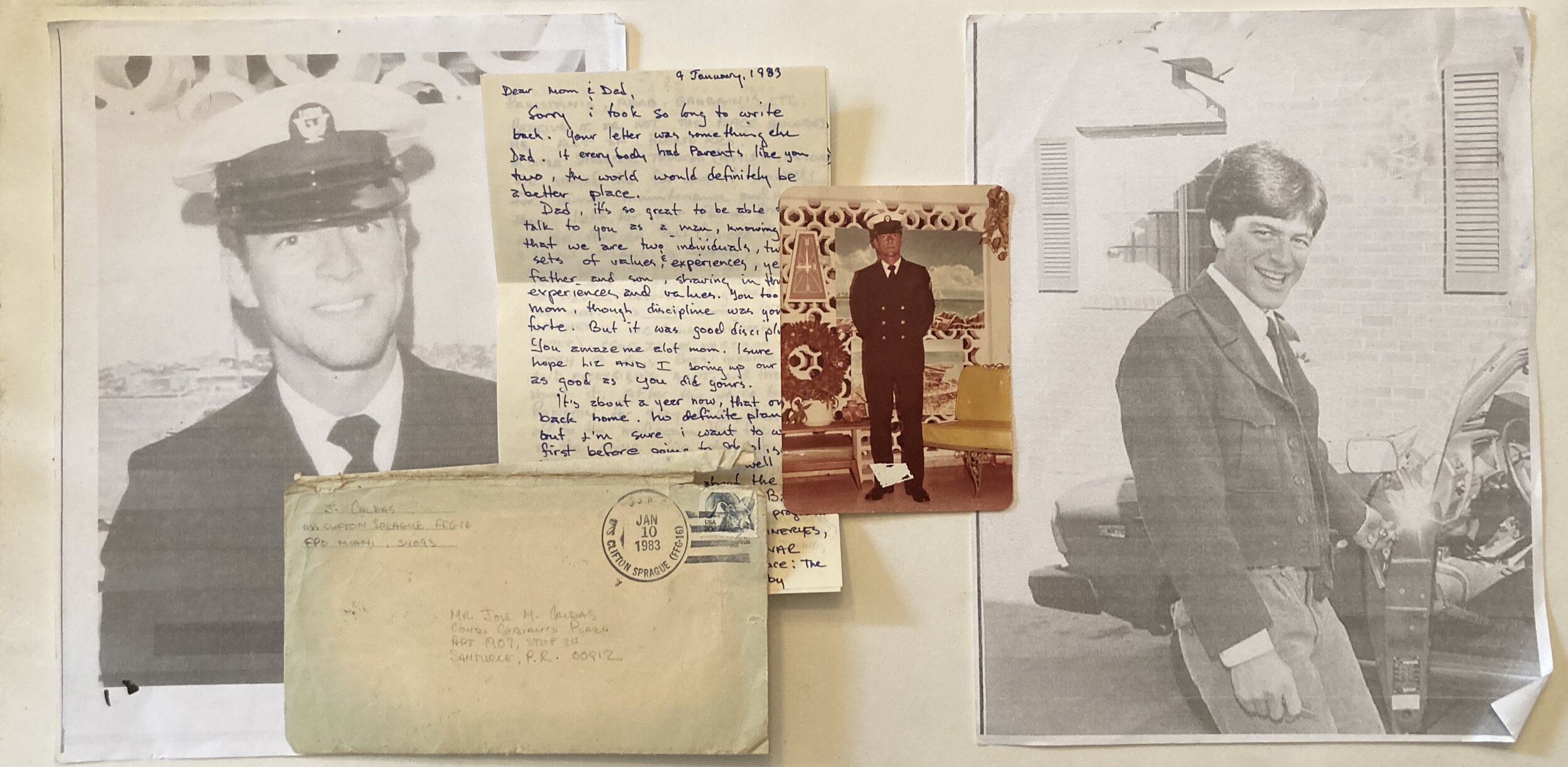

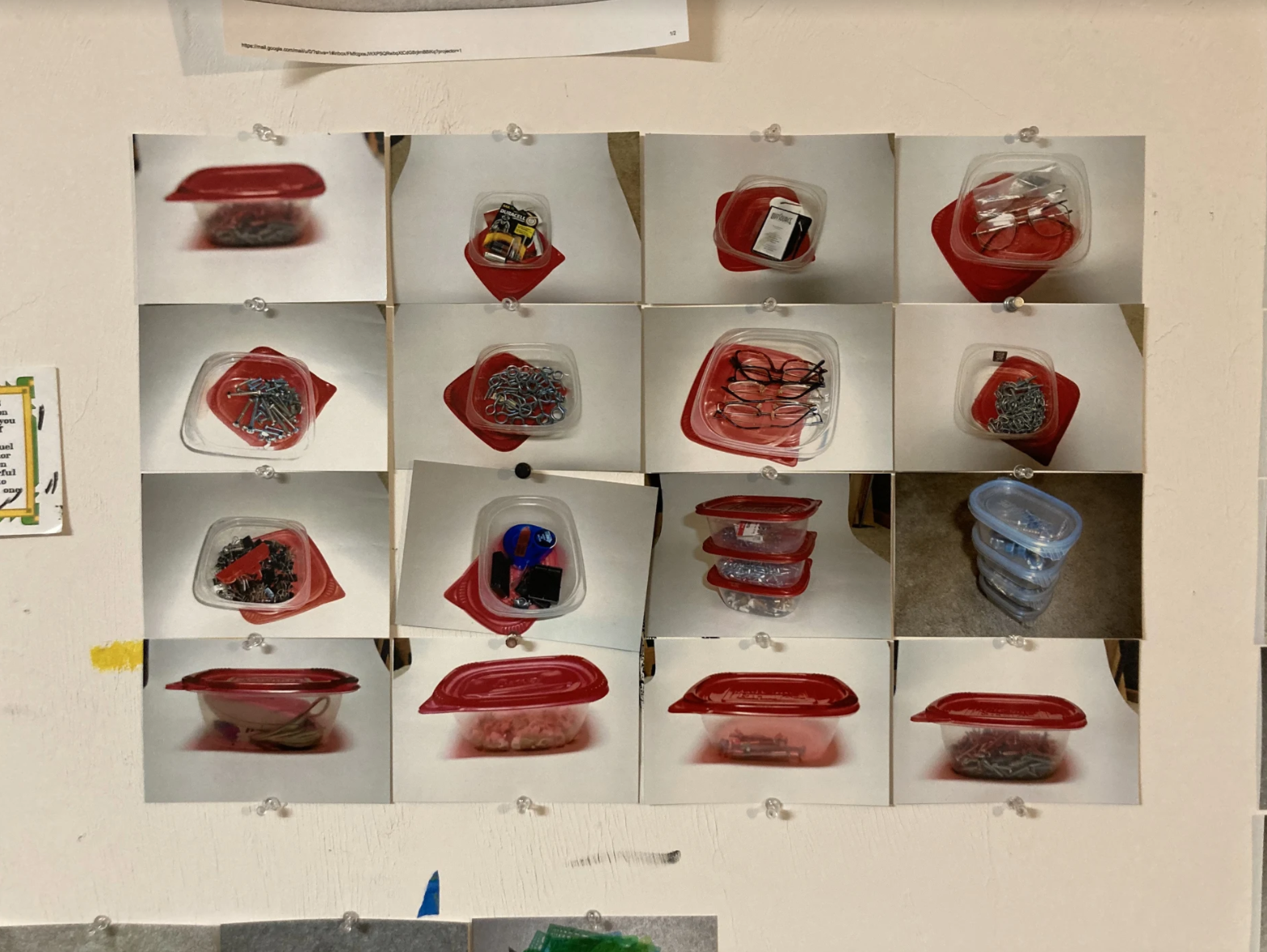

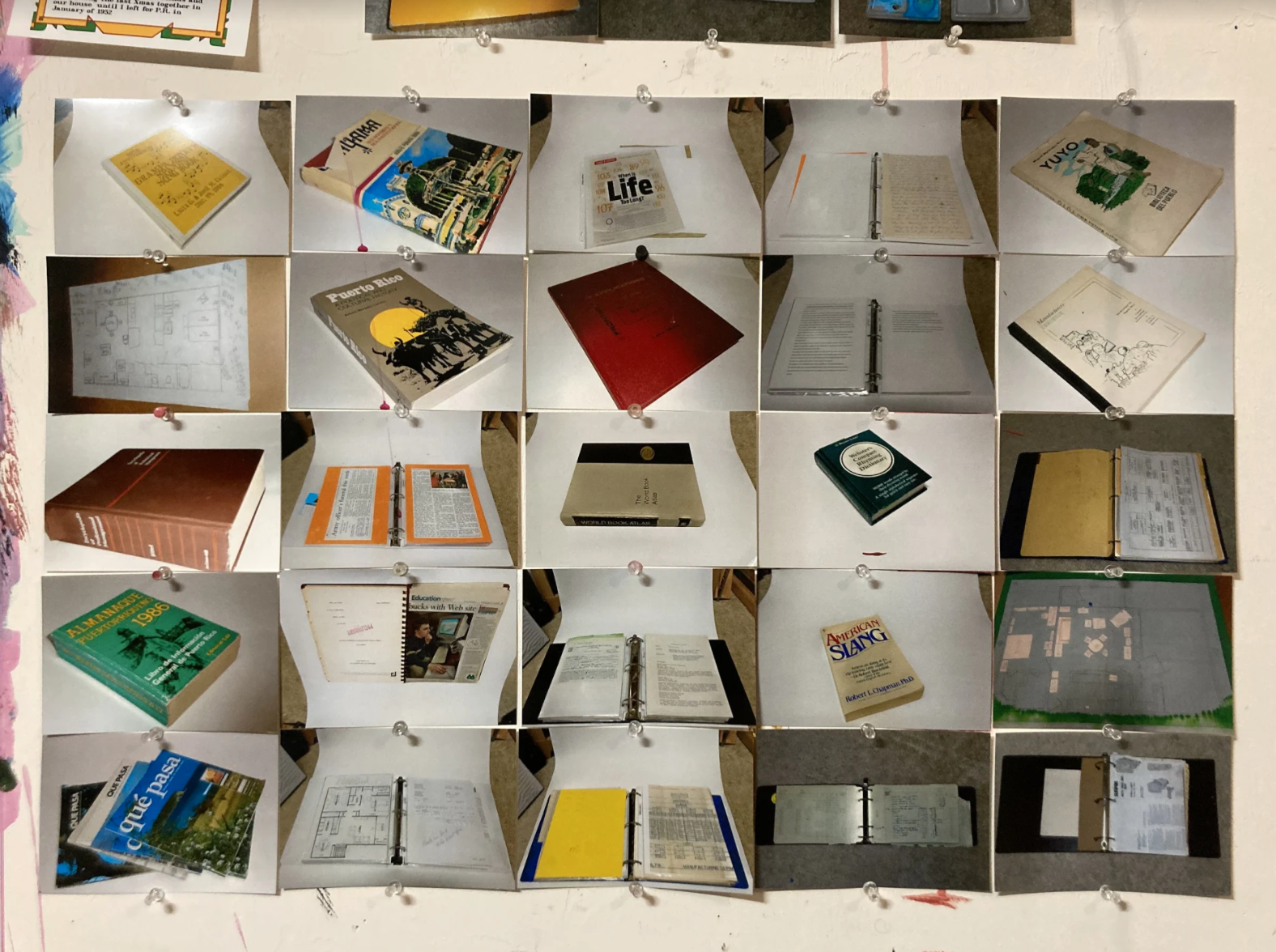

When my Grandfather, Jose Manuel Caldas, passed away he left behind hundreds of drawings and paintings, thousands of photographs, a small 5x5 foot office packed to the brim with papers and memorabilia, and as much of his memoirs as he had been able to write in the last few years of his life.

Grandpa Joe's symbols of PR

Unable to continue painting at the end of his life, because of his shaking hands, my grandfather switched to writing, and typed three three-inch binders worth of memories which only got him about as far as my youngest cousin Javier’s birth and the disappointment of my mother and father’s separation and divorce.

After he passed away, I spent two weeks with my grandmother pouring through these memoirs and his Knick knacks and photos, trying to learn more about this man. We’d spent plenty of time together when I was a child spending summers in Texas with my grandparents, but it had been some time since regular trips were possible for me. In the past, I had loved watching Grandpa Joe paint and loved watching the movies he liked. In the present, I relished the time spent with my grandmother, because she was like my grandfather, a storyteller, but she chose to recite her memories rather than writing them down. She could go for hours without stopping, seamlessly transitioning from one story to the next, whether or not they were related, and I recorded many hours of her speaking nonstop while I was with her. I marveled at her memory, and Grandpa Joe’s, and I wished, probably like all children and grandchildren do, that I had spent more time listening before. Even then, I knew I wanted to do something with these stories. Something in my language of story telling which is centered in my artistic practice.

I was pregnant with my daughter when the treasure of Grandpa Joe’s life, my grandma Ligia, died years later and I had yet to do very much artistically with the stories I knew waited for me. I mourned this loss deeply for several reasons – I had hopes that she would meet my daughter. I had hopes I’d get to listen to her tell me more stories about her life and grandpa’s life as children and a young married couple. I’d even hoped she’d tell me more about my time as a child with her and grandpa, as I tend to suffer from a bad memory when it comes to my childhood. I wanted to learn more about story telling from her, so I could learn how to do it better for my daughter.

I also knew by then that I associated my relationship with my grandparents and their stories as my one truest and strongest ties to being Puerto Rican. My feelings about my claims to my Puerto Rican blood were fraught and so ties like this held a magnitude of importance.

This loss motivated me to finally spend the time with Grandpa Joe and Grandma Lee’s stories and memories, the ones they had recorded and the few I had recorded for them. This loss combined with the arrival of my daughter has motivated me to collect and cherish what it is and has been to be Puerto Rican for my family before me, so my daughter and I can figure out what it means to us now.

Studies for your see your life passing right before your eyes as you live it 03

Studies for the prodigal son

studies for the life she was accustomed to

My grandfather’s words are bright and hopeful and full of joy and pride. Reading them, and really absorbing them is a slower process than I imagined it would be. I’ve been working on transcribing his words while simultaneously researching his stories for the better part of this year and I’ve barely finished the first chapter (although I will say my grandfather’s definitions of chapters are fairly loose and it covers quite a bit of ground). The greatest joy has been being reminded that my father inherited Grandpa Joe’s love of story telling and strong memory and almost every paragraph, page or section of the memoir can be run by him for confirmation and additional thoughts and details. I am reminded that my father, as well as my aunts and uncles, and even their cousins and mine, are additional ties I have to my Puerto Rican story.

My Puerto Rican story feels distant to me most of the time. When I am with my aunts and uncles, my cousins, or when my father tells me stories, I can feel as close to it as the actual blood in my veins. Just as often, though, being with them can make me feel even further from it. I don’t speak Spanish. I’m learning, kind of, and can understand a lot, kind of. I am the only one in my family who hasn’t been to the island. I was supposed to go this year for the first time. The trip is postponed, indefinitely. I am a Bad Puerto Rican (a joke, but still…).

I fear I may miss seeing this place that I miss despite never having been. Fenweh is a word I learned through Michael Twitty’s memoir, The Cooking Gene. It is the feeling of longing and nostalgia one has for a place they have never been. I asked my dad if there is a Spanish equivalent because I know that is the feeling I have for Puerto Rico. It’s a bit more “woo woo” than I am accustomed to holding belief for, but it also feels right, particularly the sense that it is tied to ancestral lineage and connection.

But the problem then becomes, for me, that our blood isn’t actually tied to the island as far back as all that.

I knew before diving into the memoirs that I was also interested in the larger picture of Puerto Rican history and the island’s relationship to the states. It’s an impossible relationship to ignore given current events that surround these countries. I have been struck, then, by my Grandfather’s less than political take on his childhood. As my father says, “’he was not an independentista.” He believed himself to be as fully American as any other American, whether born on the island or not:

“I have never considered myself, or my family, as a minority in this great county because to do so would be denying the basic fact that in our true democracy, the political majority of citizens rule, regardless of origin, religious beliefs, ethnic origin, or sex. Wherever we were, I lived with the knowledge that my full rights were those of American Citizens, and that accepting accommodative minority rights was an abdication of full and equal citizenship that perpetuates an unsavory situation for some individuals that would be better off demanding their full American rights.”

It is hard for me, contemporarily, to read this statement. I understand what he was probably thinking, and I certainly understand the undercurrent of “American Dream” that shoots through this statement. But it ignores the reality of the colonial relationship that took the island and puts those marginalized communities that suffered at the hands of white supremacy within the United States, which easily transferred to brown folks from an island like Puerto Rico, and places the blame at their feet for accepting anything less than the “American Dream”, which was never equally offered them. And that story continues today as Puerto Ricans remain marginalized (unless they are White enough, American enough to pass and even then…). What would he think now of how our country treats the people of his home? Would he still be pro commonwealth? Would he become an independentista? We are Bad Puerto Ricans (a joke, but still…).

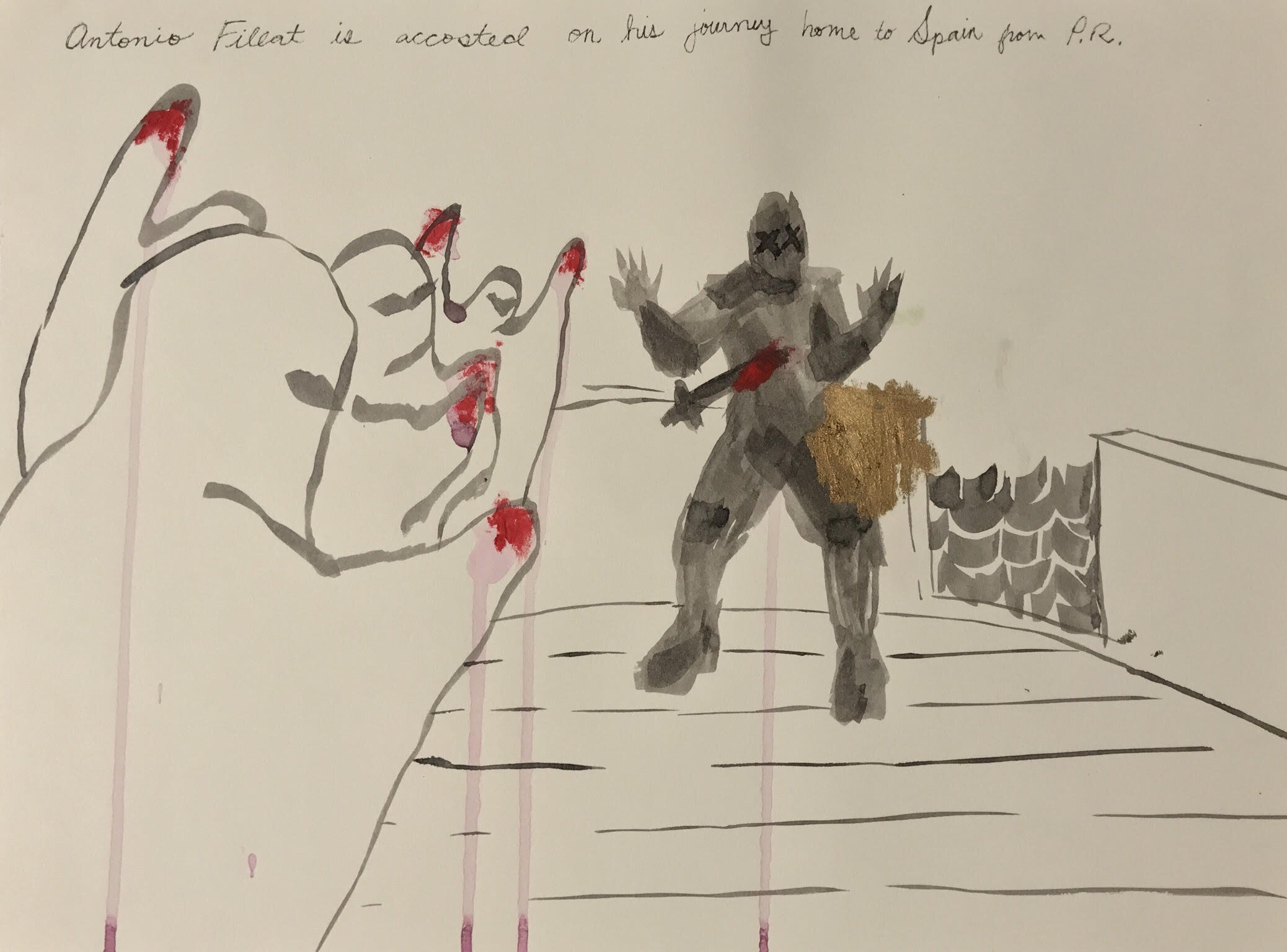

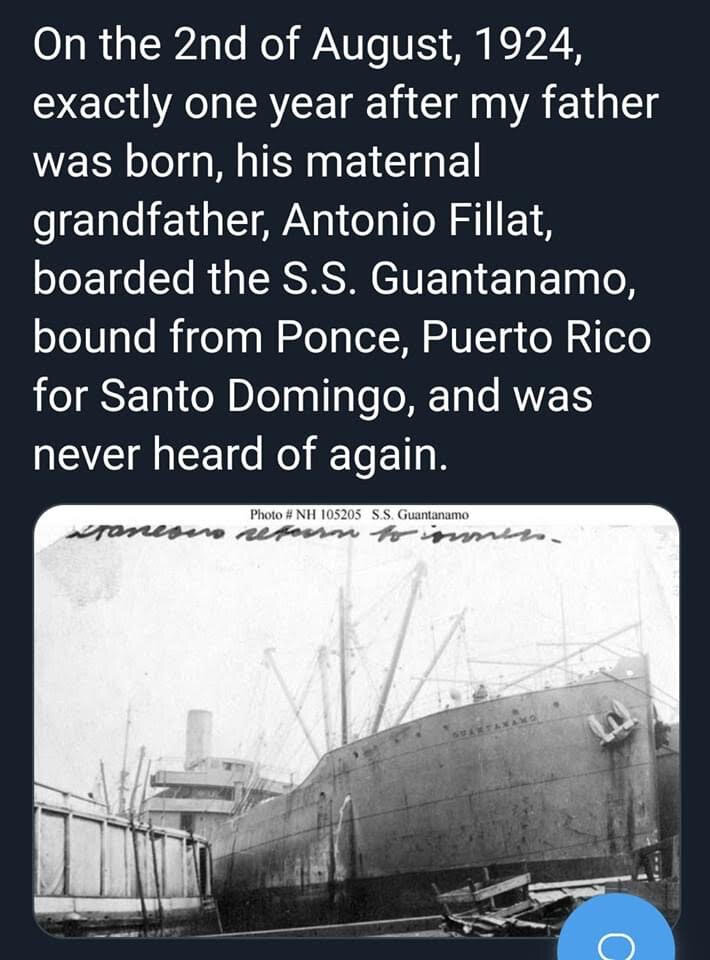

His telling of the transfer of power from Spain to America feels devoid of political commentary or insight. We know his grandfather, Antonio Fillat, was disliked and that he and his family were threatened by the violence of locals dissatisfied with Spaniards on the island. Family lore says Antonio and his family were given asylum and saved by the U.S. Army base on the outskirts of Ponce.

And that is the key. My family is Puerto Rican of Spanish descent. We are the colonizer and the colonized. We are Bad Puerto Ricans (a joke, but still…)

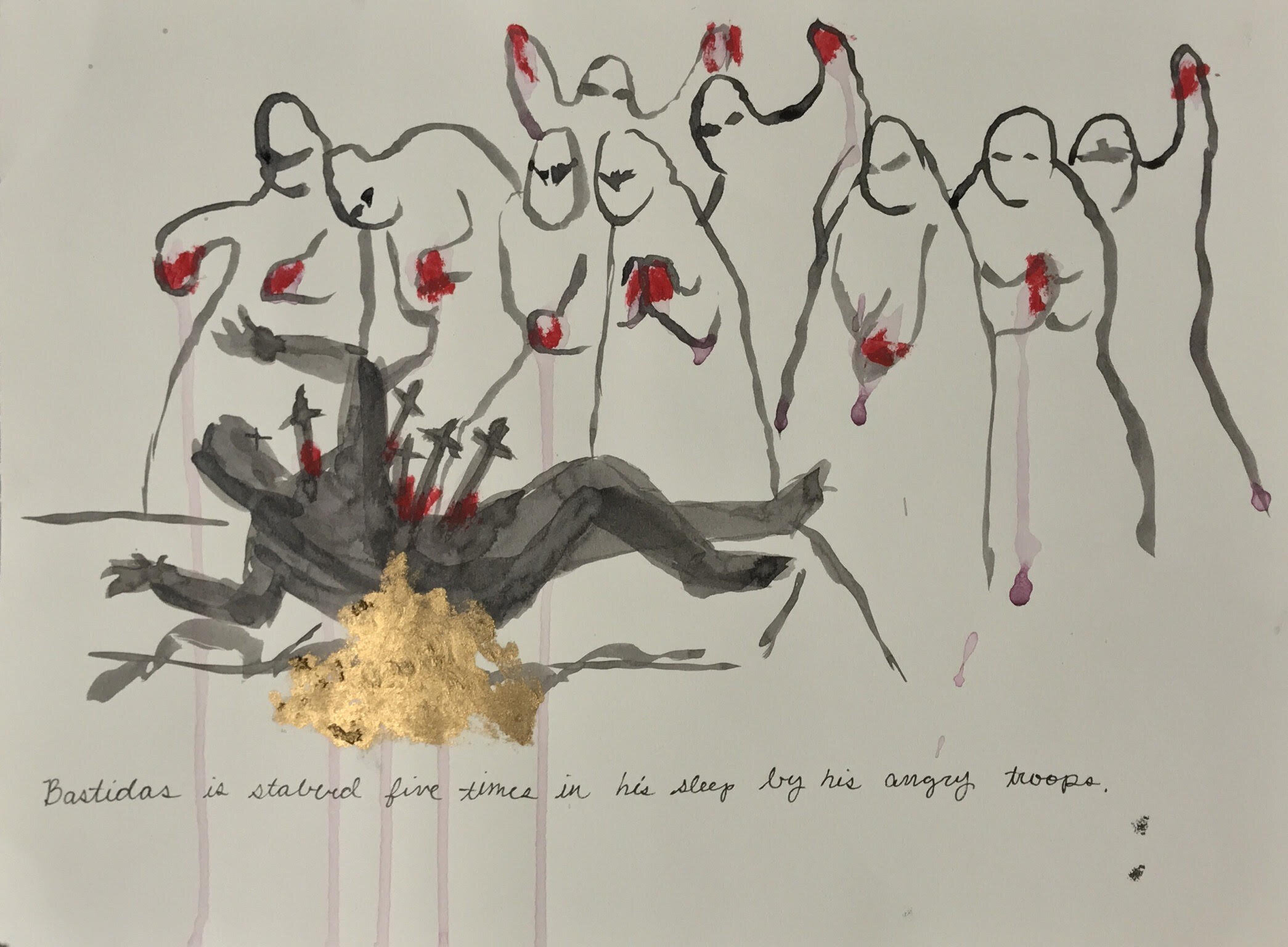

Grandpa Joe’s stories, especially from his youth, center family lore. The pride my great grandfather had in the supposed ancestral tie we had to a Spanish Conquistador Rodrigo de Bastidas. Supposedly the “noblest conquistador” of Spain, it’s easy to see that he was of his ilk, a white European colonizer spreading violence across the globe. A few pages later, our blood is tied to Franciso Jose de Caldas, “el mago de la montaña”, the mountain magician. This discoverer of hypsometry was also a Colombian revolutionary, turning church bells into cannons to fight the Spanish. When he was killed by a Spanish general, the general exclaimed “España no necesita sabios!” “Spain doesn’t need wise men!”

Studies for your see your life passing right before your eyes as you live it 02

These two stories that have become family lore, unprovable but held onto so tightly by our blood, feel like the cornerstones to my struggle with my Puerto Ricanness, my whiteness, the space I take up, and the knowledge I have and don’t have about my family.

There is so much more I have to learn. Even as I gather up the knowledge around me and think about how I will tell this story I cannot help but think, I am a Bad Puerto Rican ( joke, but still…)

Studies for who is grandpa, 1-5

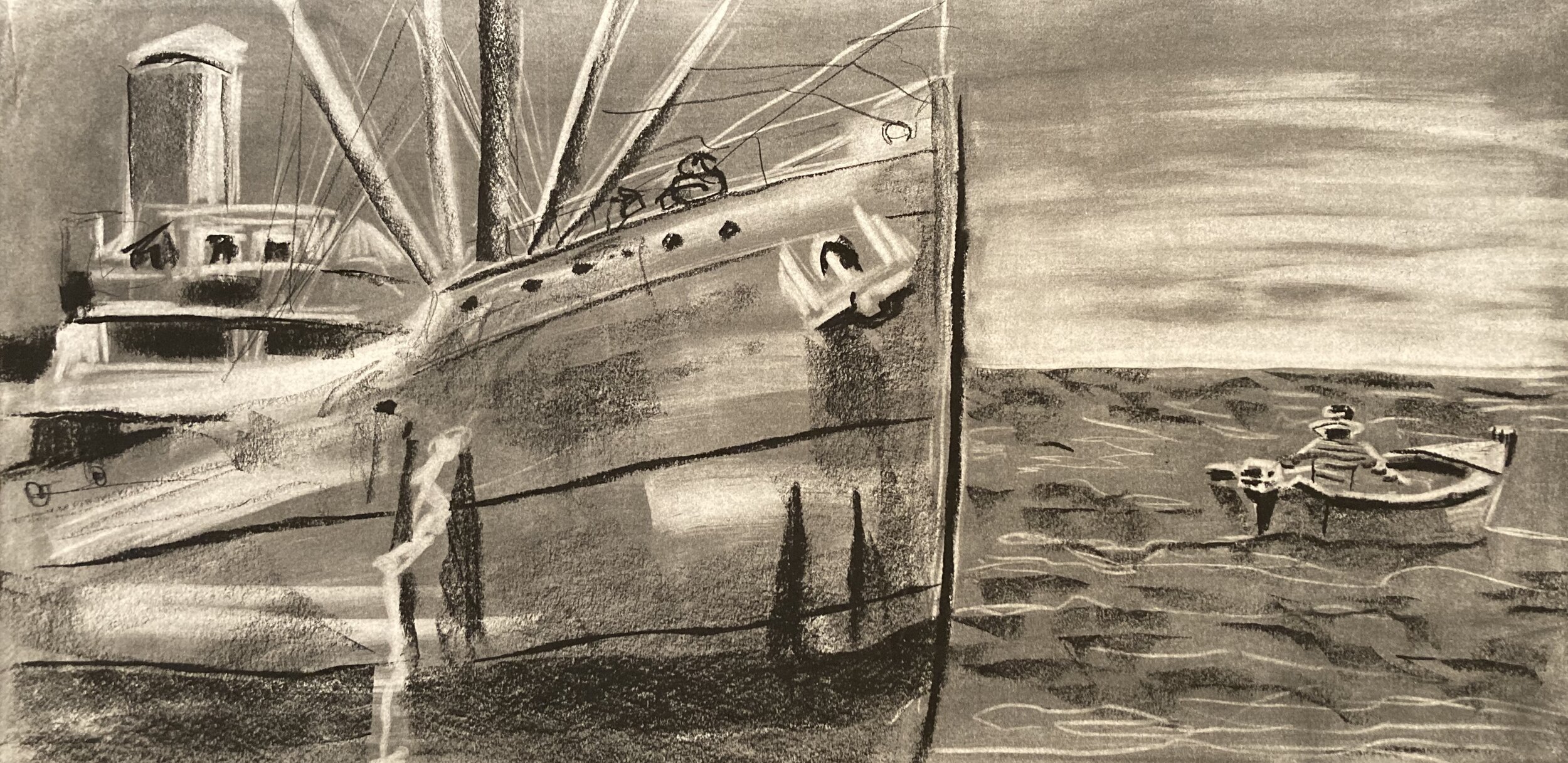

A study of economic diversity - the SS Boricuan and a Fisherman's boat

Antonio Fillat is accosted on his journey home

Bastidas is stabbed 5 times by his angry troops

Spains Noblest

What Rodrigo de Bastidas Says

The blood and bond between them