interview: hutchinson [Michi Meko]

My brother taught me to fold paper airplanes in the back of church. While the preacher did his thing, we did ours. After church we would launch white sheets of paper from the porch of God’s flight station. The lofting of airplanes into the air is a freeing gesture, one that instantly provokes the smile of a child in a toy store with a hard earned allowance-- a smile I still get to this day when lofting planes. The funny thing that’s cemented in my brain is learning the fold. Now, I believe there is a collection of knowledge in the lesson. A technique handed to me by my brother that we all remember into adulthood. I bet you can still fold your first paper jet plane, and I bet the joy of flight is still the same.

This brings me to the works of Christopher Hutchinson and the idea of flight. Folding the same paper planes from his childhood memories, he prepares us for a great voyage.

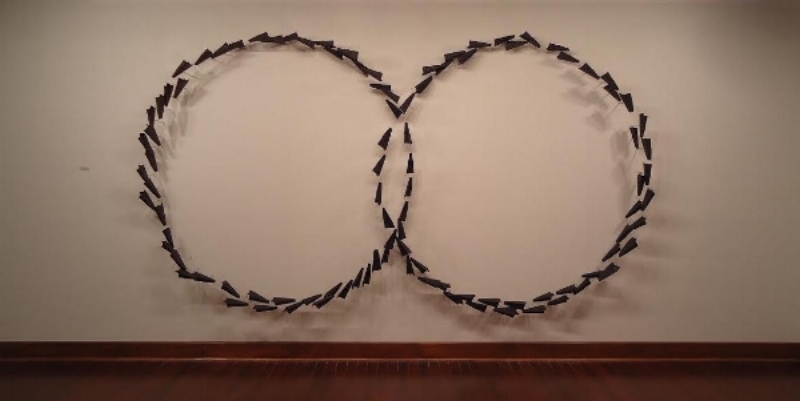

Not just any old trip from the porch of a church, but a massive movement of paper planes in formation, in charge of their own destiny and flight schedules. Simple yet beautiful arrangements of innocent paper planes that appear to the imagination like a fleet of stealth bombers ready for battle; I wonder where they are traveling so boldly. They have not a care or concern in the world for idle flights. Theirs is a serious mission. Could a paper airplane even be taken out of its playful innocent context; and if so, how would it arrive at this conclusion? Like the folding of the plane itself, it’s quite simple to Hutch…MAKE THEM BLACK

Michi Meko (MM): Can you give us a small glimpse into your early life and how that has shaped your think about the works you produce?

Christopher Hutchinson (CH): Great question…I was born and raised in Spanish Town, Jamaica with a love of my people. The Jamaican Motto is “out of Many, one people”. This, along with a very rigid religious upbringing, heavily influences me as an individual.

The goal of the work is to express the unification in the Motto “out of many, one people”. The rigid religious influence works through recognition of the binary. Good vs evil. The goal of the work is to achieve a pure, good black.

MM: What is your interest in art history? I’m more interested specifically in the post-colonial understanding of art history and how that relates to your practice. Can you help me under this thought?

CH: I have always loved everything about art, but art history gives a certain context to why something actually makes an impact that transcends time.

For me post-colonialism is a real space where the indigenous aesthetic is valued for its contribution without depending upon Western validation. But it is not only limited to aesthetic; it is also a methodology. When Jamaica became independent, one of the first acts was to change the money and the flag. So when the dialogue of Harriet Tubman on the $20 …that’s postcolonial.

MM: What are some of the specific investigations of your work?

My practice deals with black as the ideal-- where there is no inferiority and, at the same time, is not threatening.

MM: For you, as an artist is there a hindrance in the use of the color Black? We know that dictionary terms usually point to a negative. How does your understanding of the color Black factor in the context of your work. Is it any different than, let’s say, Red?

CH: Initially, during my early painterly career, the use of black was forbidden especially in realism. Black isn’t really welcomed in abstraction as well…not without meaning the binary evil. The tar paper pieces moved the black physically to the front so that it would not be shadow but instead seen as an object. With the tarpaper I wanted to achieve black as a gift. Thinking of the strips as ribbons and ties. If I can achieve an aesthetic beauty with tar paper, then tar baby would no longer have a negative perception to black folks.

MM: For the Tar works, it’s easy for the viewer to maybe look at the works of Robert Morris, Joseph Beuys, possibly Chakaia Booker, and to make quick associations that connect readily available images of art history and compartmentalize the works’ understanding into lazy answer. I am more interested in how these works (the Tar Paper) separates itself from these individuals and how it relates, if at all, to the modes of making say a David Hammond’s or the complex use of simple objects of say a Thornton Dial.

CH: Robert Morris is the closest of the 3 because of the simplistic relationship to material and ALLOWING THE MATERIAL TO DIRECT the thought. The great Hammonds and Dial are way freer than I am. I am limited to the beauty and purity of blackness.

MM: Are the folded objects a product of outsourcing made by another’s hand? Or are they part of a ritual practice or meditation that lets one get further into the understanding through the repetition of process? In this process is there then a plague of repetition? Is that even a concern?

CH: My wife and I folded 1000 planes for this exhibition. The designs are not outsourced. This is the actual plane I threw when I was in Jamaica. They are a symbol of pure childhood experience -- before a true understanding of Race and Religion.

MM: To many on the surface, what seems like a simple arrangement of folded paper airplanes is actually an elaborate, eloquent concept driving this work forward. Can you give us an understanding of these formations and what they mean to your interest in overall concept?

CH: Black Flight144 began to consider the number of years after the emancipation of slaves which began Juneteenth. Arise you god, Moving forward together, Already home, forever ever, ever, ever, flight of the bumblebee.

MM: I often compare you to a Hip Hop version of famed art critic Robert Hughes. Where can one read your critical writings?

CH: https://creativethresholds.com/?s=Postcolonial&submit=Search

Christopher Hutchinson is an accomplished Jamaican conceptual artist, professor and contributor to the art community as a writer, critic and founder of the nonprofit Smoke School of Art. He is a Professor of Art at Atlanta Metropolitan State College and has been featured as a lecturer including prestigious engagements at University of Alabama and the Auburn Avenue Research Library. For two decades, Chris has been a practicing artist. His works have been exhibited in internationally recognized institutions including City College New York (CUNY) and featured at the world’s leading international galleries such as Art Basel Miami. He has always had an innate passion for creating spaces where Africans and people of African descent contribute to an inclusive contemporary dialogue—ever evolving, not reflexive but pioneering. This requires challenging the rubric of the canon of art history, a systemic space of exclusion for the Other: women and non-Whites, and where necessary he rewrites it. He received his Master of Fine Arts Degree in Painting from Savannah College of Art & Design, Atlanta and his Bachelor of Arts Degree from the University of Alabama in Huntsville, Alabama.

| all content is property of the artist |