Failsafe

by Craig Drennen

In 1972 the first-grade class at Tanner Elementary school in the unincorporated community of Tanner, West Virginia staged a mock presidential election. The two candidates in this mock election were the same two candidates running for the United States presidency that year: George McGovern and Richard Nixon. There was great excitement among the students as the date of their mock election approached. When that day finally came the 6-year old’s in that small school in a remote, isolated county voted overwhelmingly for Nixon. I was one of the six-year old’s in that class. I voted McGovern.

Also in 1972, an aeronautics engineer and a naval engineer built and tested a rocket-powered motorcycle they named Skycycle X-1. In 1974 an updated version was built for daredevil Robert Craig Knievel, known professionally as Evel Knievel, for a highly publicized effort to jump Snake River Canyon in Twin Falls, Idaho. Knievel gained national acclaim partly due to a botched attempt at jumping the Caesar’s Palace fountains in Las Vegas in 1967. As a former insurance salesman, semi-pro hockey player, and journeyman car show performer, Knievel had no knowledge of the physics of stunt jumping. He operated solely on instincts, daring, and an insatiable appetite for fame. Knievel’s activity mirrored tendencies toward endurance and danger in 1970’s performance art, but to far more spectacular effects. Knievel dressed in jumpsuits like Elvis and, with his Caesar’s Palace crash, gave us a Zapruder-level film of a man being destroyed. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kYGGCVE2lKY

On September 8, 1974, seven years after the Caesar’s Palace crash and three years before his eventual assault conviction, Evel Knievel tries to jump Snake River Canyon. The parachute of the Skycycle X-2 deploys almost immediate after take-off. He not only fails, he fails safely. As an eight-year old watching the national news, I noticed.

Image courtesy of Adam Savage’s Tested (https://www.tested.com)

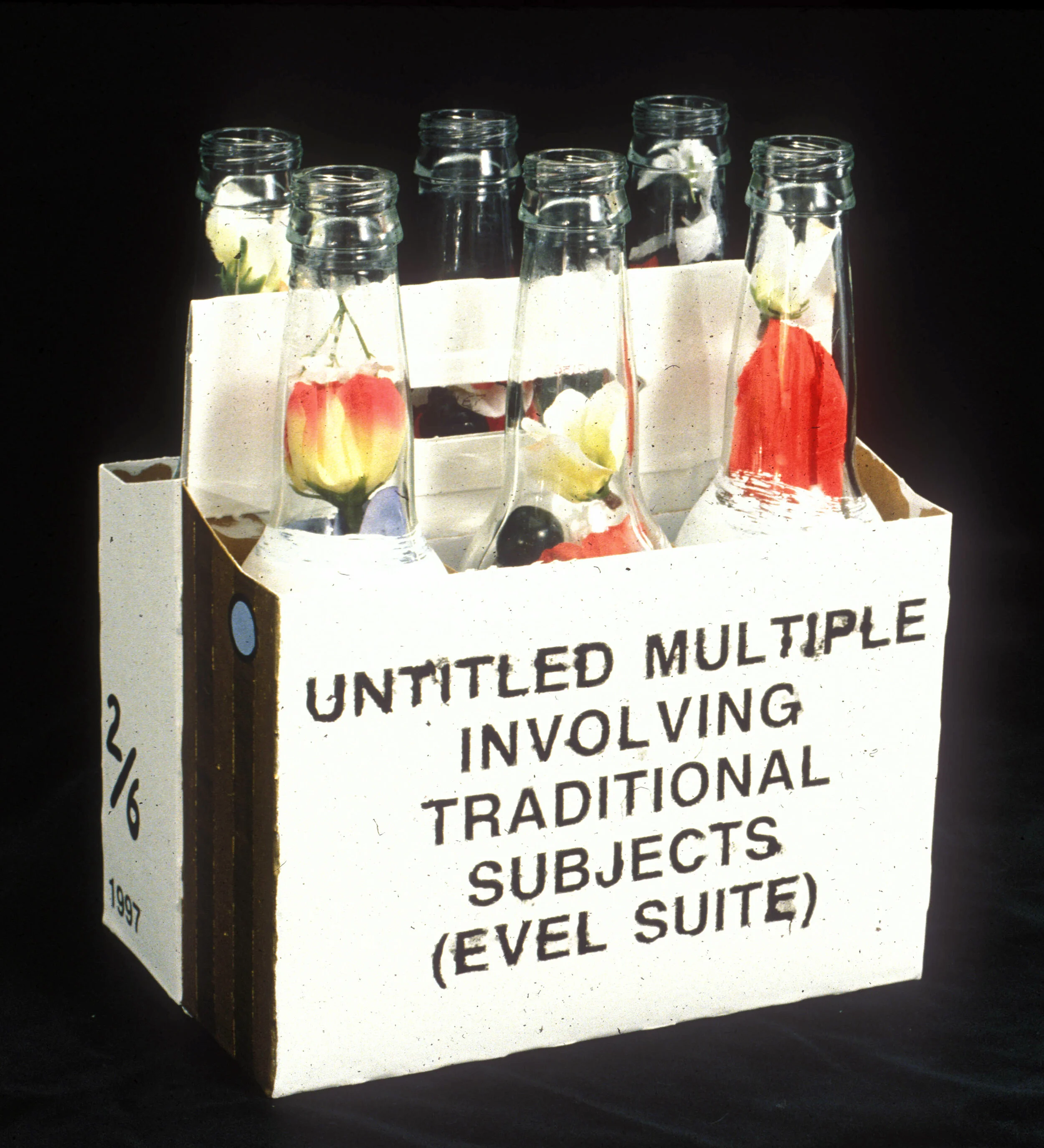

In early 1993 I moved from Lexington, Kentucky to New York City. After my first job at the Strand Bookstore I moved on to art handling jobs and adjunct teaching. I joined a shared studio on west 27th Street to get my studio practice off the ground. I fumbled through some early paintings and found myself struggling to survive. In an art world full of Nixons, I was still a McGovern. Looking back on those years, it seems clear that a large part of my difficulty in the studio stemmed from the fact that I did not believe my own subjectivity warranted being present within my own work--and I didn’t yet have the tools to bridge that gap and recuperate. So I continued to fail. In 1996, partially as a joke to myself, I began producing handmade multiples about my unsuccessful painting practice. The first multiple was Untitled Multiple Involving Traditional Subjects (B.I.J.S.P.) and it’s in that piece that I devised the premise. I’d decided that every six paintings I would stop and make a multiple from altered six-packs. On each bottle I put the title of the painting to which it referred. The “B.I.J.S.P.” part was the first initial from each of those six titles. The next multiple was dedicated to four pieces inspired by Mensa, the international genius I.Q. society. The third multiple was Evel Suite based on six paintings about Evel Knievel and his Snake River Canyon jump. These multiples were an aberration in my artistic thinking at that time, sparked by frustration and dissatisfaction. I had to make each number in the edition by hand because I didn’t know how to do anything else. I painted the bottles and cardboard cartons with white primer. I transferred the text using reversed photocopies and lacquer thinner, each bleeding error reinforced with sign painter’s enamel. I saw this entire process as me producing abbreviated CliffsNotes™ for my paintings as if they were beloved classics. They were abbreviations of paintings that few people knew about and even fewer saw, but suddenly obscurity seemed less like a poison and more like a vitamin. I had accidentally stumbled onto a way to fail productively.

And it was hilarious.